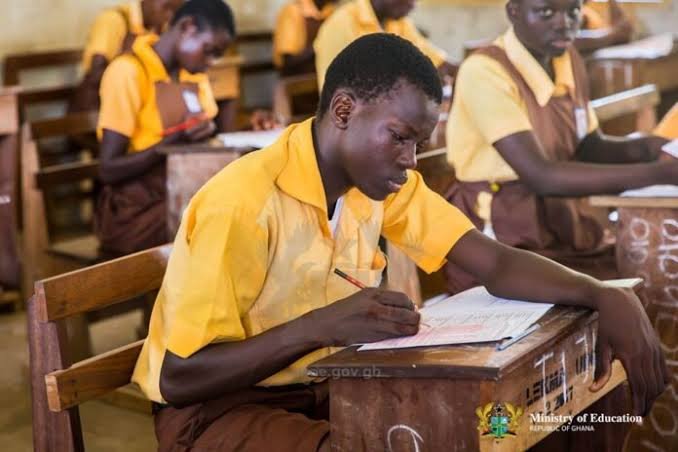

The Ghanaian government has announced a major change in its education system, all teachers must now teach using local languages as the main medium of instruction at the basic school level.

Education Minister Haruna Iddrisu made the announcement on Friday, October 24, describing it as a bold move to improve learning outcomes and preserve the nation’s cultural heritage.

“From today, the use of mother-tongue instruction by teachers is compulsory in all Ghanaian schools,” he declared.This decision marks a significant shift from the long-standing dominance of English in Ghana’s education system.

The idea isn’t entirely new and already enjoys global support. Studies by UNESCO and the World Bank have consistently shown that children grasp concepts faster and learn more effectively when taught in their native language, particularly during early childhood education.

For Ghana’s leaders, the policy is also about reclaiming cultural identity. After decades of English serving as the main instructional language, a colonial legacy, the government says it’s time for schools to reflect the country’s linguistic roots.

Similar moves are also being explored in other African nations like South Africa, Kenya, and Tanzania.

However, implementing this policy won’t be easy.Ghana has over 70 languages, with 11 officially recognized for education and media use, including Akan (Twi and Fante), Ewe, Ga, Dagbani, Nzema, and Gonja.

This diversity poses a practical challenge: how do you select one language in classrooms where students speak multiple mother tongues?

In major cities such as Accra and Kumasi, where children come from varied ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, the government says instruction will be in the “dominant local language” of each area though defining that can be complex.

Most textbooks are written in English, and translating them into multiple local languages, alongside training teachers and maintaining quality, could take years.

“We already struggle to get enough materials in English,” said a teacher in Accra during an interview with a local radio station. “Now we’ll need books and training in ten different languages. It’s a great idea, but we’re not ready,” added Freda Serwaa, a basic school teacher from Kumasi.

This isn’t Ghana’s first attempt at such a policy. A similar initiative was introduced in the early 2000s but faded away due to weak implementation, limited resources, and resistance from parents who feared it would hinder their children’s English fluency.